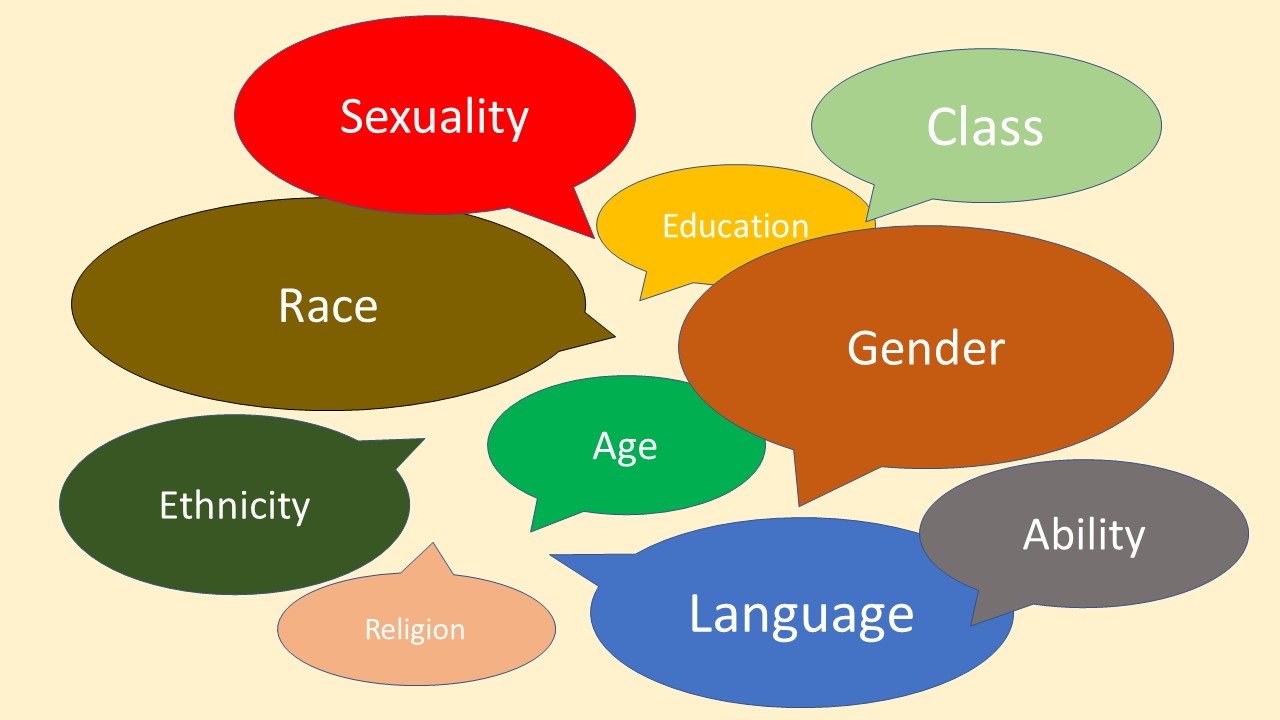

This seminar is situated in the broad field of sociolinguistics, i.e. the study of the relationship between language and society, drawing also on the theories of Gender, Queer, and Cultural Studies. As Fishman put it, sociolinguistics deals with “who speaks (or writes) what language (or what language variety) to whom and when and to what end” (1972: 46). In this seminar we examine the role of language in a variety of social contexts in order to develop insights into how language works and how it can be used to signal identities and to convey social meaning. We investigate the positioning of categories such as race, class, and gender in social and historical contexts and analyze how individuals negotiate these positionings. This class focuses on linguistic variation in a two-fold way, i.e. by focusing both on language use and on the user. Students will learn the basic terminology and main strands of sociolinguistic research; classic approaches in sociolinguistics will be complemented by more recent research. By integrating AI tools like ChatGPT in our class, students can carve out language patterns and trends, thus enriching their understanding of the complex interplay between language and society.

References:

Eckert, Penelope. 2012. Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology. 41. 87-100.

Eckert, Penelope. 2018. Meaning and Linguistic Variation: The Third Wave in Sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Holmes, Janet & Nick Wilson. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, 5th ed. New York: Routledge.

Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2006. Introducing Sociolinguistics. London: Routledge.

Trudgill, Peter. 2000. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

Multilingualism is the norm, not the exception. People draw on a vast array of linguistic resources as they engage in heterogeneous linguistic practices.

Multilingualism […] should not be seen as a collection of ‘Languages’ that a speaker controls, but rather as a complex of specific semiotic resources, some of which belong to a conventionally defined ‘language,’ while others belong to another ‘language.’ The resources are concrete accents, language varieties, registers, genres, modalities […] (Blommaert 2010: 102)

This seminar offers an introduction to the many facets of multilingualism in a linguistically diverse world. We will provide an introduction to some fundamental issues in multilingualism research and give an overview of much-discussed key concepts such as diglossia, minority and majority languages, heritage languages, heteroglossia, code-switching, translanguaging, border languaging, and many more.

This seminar will introduce some key theoretical and methodological approaches to multilingualism and outline the struggles in defining ‘language’ and ‘multilingualism’ (and plurilingualism, and plurimultilingualism for that matter). Focusing on standard languages, global languages and language making (Krämer 2023 forthcoming) helps questioning the boundaries of ‘languages.’ We will also address issues of language policy and language ideologies when tackling the interplay of individual and societal multilingualism.

Blommaert, Jan, and Ben Rampton. 2016: “Language and Superdiversity.” MMG Working Paper 12-09. www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers.

Coulmas, Florian. 2018: An Introduction to Multilingualism: Language in a Changing World. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Gramling, David. 2016: The Invention of Monolingualism. New York and London: Bloomsbury.

Horner, Kristine, and Jean-Jacques Weber. 2018: Introducing Multilingualism. A Social Approach. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Nossem, Eva. 2023: Border Languaging: Multilingual Practices on the Border. Nomos.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

- DozentIn: Yuliya Stodolinska

In the course of the last years, the world has plunged from one crisis to another – from the financial crisis in 2008/09 and the refugee crisis (or migration crisis or solidarity crisis) in 2015, to the corona crisis or health crisis since 2020, to today’s energy crisis and information crisis. Of course, crises have also existed beforehand – let’s just think of the oil crisis in the middle of the last century, the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, and many more. All the crises, and also the current war in Ukraine (sometimes even phrased as ”Ukraine crisis”!) are always fought out also on a discursive level.

This seminar is drafted as an introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis or Critical Discourse Studies in the field of linguistics. According to van Dijk (1998a), Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a field that is concerned with studying and analyzing written and spoken texts to reveal the discursive sources of power, dominance, inequality, and bias. It examines how these discursive sources are maintained and reproduced within specific social, political and historical contexts. By ‘critical’ discourse analysis, [Fairclough] mean[s] discourse analysis which aims to systematically explore often opaque relationships of causality and determination between (a) discursive practices, events, and texts, and (b) wider social and cultural structures, relations and processes; to investigate how such practices, events and texts arise out of and are ideologically shaped by relations of power and struggles over power; and to explore how the opacity of these relationships between discourse and society is itself a factor securing power and hegemony (1993: 135).

In this seminar, we will consider language as a social practice and investigate language use as both socially shaped and also socially shaping. Particular focus is laid on the analysis of discursive practices which have emerged in the context of the various current crises and on how crises are constructed discursively.

Bibliography

Barker, Chris (2001): Cultural Studies and Discourse Analysis: A Dialogue on Language and Identity. London: Sage

Fairclough, Norman (1989): Language and Power. Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman

Leeuwen, Theo van (2008): Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Wodak, Ruth (2009): Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Wodak, Ruth (2020): The Politics of Fear: The Shameless Normalization of Far-Right Discourse. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

Young, Lynne, and Bridgit Fitzgerald (2017): The Power of Language. How Discourse Influences Society. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing.

Additional readings assigned in class.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

Multilingualism is the norm, not the exception. People draw on a vast array of linguistic resources as they engage in heterogeneous linguistic practices.

Multilingualism […] should not be seen as a collection of ‘Languages’ that a speaker controls, but rather as a complex of specific semiotic resources, some of which belong to a conventionally defined ‘language,’ while others belong to another ‘language.’ The resources are concrete accents, language varieties, registers, genres, modalities […] (Blommaert 2010: 102)

This seminar offers an introduction to the many facets and conceptualizations of multilingual practices. We will provide an introduction to some fundamental issues in multilingualism research and give an overview of much-discussed key concepts such as multilingualism, plurilingualism, code-switching, translanguaging, metrolingualism, border languaging and many more.

This seminar will introduce some key theoretical and methodological approaches to multilingualism and outline the struggles in defining ‘language’ and ‘multilingualism’ (and plurilingualism, and plurimultilingualism for that matter). Focusing on standard languages, global languages, as well as pidgins and creoles helps questioning the boundaries of ‘languages.’ We will also address issues of language policy and language ideologies when tackling the interplay of individual and societal multilingualism.

Selected Readings:

Blommaert, Jan, and Ben Rampton. 2016: ”Language and Superdiversity.” MMG Working Paper 12-09. www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers.

Coulmas, Florian. 2018: An Introduction to Multilingualism: Language in a Changing World. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Creese, Angela, and Adrian Blackledge (eds). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Superdiversity. London: Routledge.

Garcia, Ofelia, and Li Wei. 2014: Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gramling, David. 2016: The Invention of Monolingualism. New York and London: Bloomsbury.

Horner, Kristine, and Jean-Jacques Weber. 2018: Introducing Multilingualism. A Social Approach. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Pennycook, Alastair, and Emi Otsuji. 2015: Metrolingualism: Language in the City. New York: Routledge.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

This seminar is situated in the broad field of sociolinguistics, i.e. the study of the relationship between language and society, drawing also on the theories of Gender, Queer, and Cultural Studies. As Fishman put it, sociolinguistics deals with ”who speaks (or writes) what language (or what language variety) to whom and when and to what end” (1972: 46). In this seminar we examine the role of language in a variety of social contexts in order to develop insights into how language works and how it can be used to signal identities and to convey social meaning. We investigate the positioning of categories such as race, class, and gender in social and historical contexts and analyze how individuals negotiate these positionings. This class focuses on linguistic variation in a two-fold way, i.e. by focusing both on language use and on the user. The students of this class will learn the basic terminology and main strands of sociolinguistic research; classic approaches in sociolinguistics will be complemented by more recent research.

References:

Alim , H. Samy, John R. Rickford, and Arnetha Ball, ed. 2016. Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes our Ideas about Race. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bucholtz, Mary and Kira Hall (eds). 1995. Gender Articulated: Language and the Culturally Constructed Self. New York: Routledge.

Eckert, Penelope. 2012 Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology. 41. 87-100.

Holmes, Janet & Nick Wilson: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, 5th ed. New York: Routledge.

Lanehard, Sonja (ed.). 2015: The Oxford Handbook of African American Language. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Levon, Erez. 2015. Integrating Intersectionality in Language, Gender, and Sexuality Research. Language and Linguistics Compass. 9(7): 295-308.

Levon, Erez. 2015 Language, Sexuality, and Power: Studies in Intersectional Sociolinguistics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2006. Introducing Sociolinguistics. London: Routledge.

Trudgill, Peter. 2000. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

In the course of the last year, due to the health crisis evolving around the coronavirus, language has had to adapt rapidly. Not only has the Covid pandemic introduced quite an amount of epidemiological and virological terminology to the general public, but it has also led to a proliferation of neologisms and new metaphors, and new discourses have come into being to frame the developments of the pandemic.

This seminar is drafted as an introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis or Critical Discourse Studies in the field of linguistics. According to van Dijk (1998a), Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a field that is concerned with studying and analyzing written and spoken texts to reveal the discursive sources of power, dominance, inequality, and bias. It examines how these discursive sources are maintained and reproduced within specific social, political and historical contexts. By ‘critical’ discourse analysis, [Fairclough] mean[s] discourse analysis which aims to systematically explore often opaque relationships of causality and determination between (a) discursive practices, events, and texts, and (b) wider social and cultural structures, relations and processes; to investigate how such practices, events and texts arise out of and are ideologically shaped by relations of power and struggles over power; and to explore how the opacity of these relationships between discourse and society is itself a factor securing power and hegemony (1993: 135).

In this seminar, we will consider language as a social practice and investigate language use as both socially shaped and also socially shaping. Particular focus is laid on the analysis of discursive practices which have emerged over the last year in the context of the ongoing pandemic.

Bibliography

Barker, Chris: Cultural Studies and Discourse Analysis: A Dialogue on Language and Identity. London: Sage

Fairclough, Norman (1989): Language and Power. Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman

Leeuwen, Theo van (2008): Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Nossem, Eva 2020: The pandemic of nationalism and the nationalism of pandemics. In: UniGR-CBS Working Paper. Vol.8,DOI: https://doi.org/10.25353/ubtr-xxxx-1073-4da7

Wicke, Philipp and Marianna M. Bolognesi (2020): Framing COVID-19: How we conceptualize and discuss the pandemic on Twitter.” PLoS ONE 15(9): e0240010. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240010 .

Wodak, Ruth (2009): Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Young, Lynne, and Bridgit Fitzgerald: The Power of Language. How discourse influences society

Additional readings assigned in class.

This class will take place online on MS Teams & Zoom.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

This seminar is situated in the broad field of sociolinguistics, i.e. the study of the relationship between language and society, drawing also on the theories of Gender, Queer, and Cultural Studies. As Fishman put it, sociolinguistics deals with “who speaks (or writes) what language (or what language variety) to whom and when and to what end” (1972: 46). In this seminar we examine the role of language in a variety of social contexts in order to develop insights into how language works and how it can be used to signal identities and to convey social meaning. We investigate the positioning of categories such as race, class, and gender in social and historical contexts and analyze how individuals negotiate these positionings. This class focuses on linguistic variation in a two-fold way, i.e. by focusing both on language use and on the user. The students of this class will learn the basic terminology and main strands of sociolinguistic research; classic approaches in sociolinguistics will be complemented by more recent research.

References:

Alim , H. Samy, John R. Rickford, and Arnetha Ball, ed. 2016. Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes our Ideas about Race. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bucholtz, Mary and Kira Hall (eds). 1995. Gender Articulated: Language and the Culturally Constructed Self. New York: Routledge.

Eckert, Penelope. 2012 Three waves of variation study: The emergence of meaning in the study of sociolinguistic variation. Annual Review of Anthropology. 41. 87-100.

Holmes, Janet & Nick Wilson: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, 5th ed. New York: Routledge.

Levon, Erez. 2015. Integrating Intersectionality in Language, Gender, and Sexuality Research. Language and Linguistics Compass. 9(7): 295-308.

Levon, Erez. 2015 Language, Sexuality, and Power: Studies in Intersectional Sociolinguistics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2006. Introducing Sociolinguistics. London: Routledge.

Trudgill, Peter. 2000. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

Multilingualism is the norm, not the exception. People draw on a vast array of linguistic resources as they engage in heterogeneous linguistic practices.

Multilingualism […] should not be seen as a collection of ‘Languages’ that a speaker controls, but rather as a complex of specific semiotic resources, some of which belong to a conventionally defined ‘language,’ while others belong to another ‘language.’ The resources are concrete accents, language varieties, registers, genres, modalities […] (Blommaert 2010: 102)

This seminar offers an introduction to the many facets of multilingualism in a linguistically (super)diverse world. We will provide an introduction to some fundamental issues in multilingualism research and give an overview of much-discussed key concepts such as diglossia, minority and majority languages, code-switching, translanguaging, heteroglossia, and many more, including diversity, superdiversity, globalization etc.

This seminar will introduce some key theoretical and methodological approaches to multilingualism and outline the struggles in defining ‘language’ and ‘multilingualism’ (and plurilingualism, and plurimultilingualism for that matter). Focusing on standard languages, global languages, as well as pidgins and creoles helps questioning the boundaries of ‘languages.’ We will also address issues of language policy and language ideologies when tackling the interplay of individual and societal multilingualism.

- Blommaert, Jan, and Ben Rampton. 2016: “Language and Superdiversity.” MMG Working Paper 12-09. www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers.

- Coulmas, Florian. 2018: An Introduction to Multilingualism: Language in a Changing World. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Creese, Angela, and Adrian Blackledge (eds). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Superdiversity. London: Routledge.

- Gramling, David. 2016: The Invention of Monolingualism. New York and London: Bloomsbury.

- Horner, Kristine, and Jean-Jacques Weber. 2018: Introducing Multilingualism. A Social Approach. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

This seminar is drafted as an introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis or Critical Discourse Studies in the field of linguistics. According to van Dijk (1998a), Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a field that is concerned with studying and analyzing written and spoken texts to reveal the discursive sources of power, dominance, inequality, and bias. It examines how these discursive sources are maintained and reproduced within specific social, political and historical contexts. By ‘critical’ discourse analysis, [Fairclough] mean[s] discourse analysis which aims to systematically explore often opaque relationships of causality and determination between (a) discursive practices, events, and texts, and (b) wider social and cultural structures, relations and processes; to investigate how such practices, events and texts arise out of and are ideologically shaped by relations of power and struggles over power; and to explore how the opacity of these relationships between discourse and society is itself a factor securing power and hegemony (1993: 135). In this seminar, we will consider language as a social practice and investigate language use as both socially shaped and also socially shaping. Particular focus is laid on the analysis of discursive practices through which understandings, disagreements and conflicts about borders are negotiated and by and through which borders are produced.

Bibliography

Barker, Chris: Cultural Studies and Discourse Analysis: A Dialogue on Language and Identity. London: Sage

Fairclough, N. (1989): Language and Power. Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman

Koller, Veronika, Susanne Kopf, and Marlene Miglbauer, eds. (2019): Discourses of Brexit. Abingdon: Routledge.

Leeuwen, Theo van (2008): Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Wodak, Ruth (2009): Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Wodak, Ruth, and Bernhard Forchtner, eds. (2017): The Routledge Handbook of Language and Politics. Abingdon: Routledge.

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem

This seminar is drafted as an introduction to Critical Discourse Analysis or Critical Discourse Studies in the field of linguistics. According to van Dijk (1998a), Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a field that is concerned with studying and analyzing written and spoken texts to reveal the discursive sources of power, dominance, inequality, and bias. It examines how these discursive sources are maintained and reproduced within specific social, political and historical contexts. By ‘critical’ discourse analysis, [Fairclough] mean[s] discourse analysis which aims to systematically explore often opaque relationships of causality and determination between (a) discursive practices, events, and texts, and (b) wider social and cultural structures, relations and processes; to investigate how such practices, events and texts arise out of and are ideologically shaped by relations of power and struggles over power; and to explore how the opacity of these relationships between discourse and society is itself a factor securing power and hegemony (1993: 135). In this seminar we will consider language as a social practice and investigate language use as both socially shaped and also socially shaping. Particular focus is laid on the analysis of discursive practices through which understandings, disagreements and conflicts about gender, sexuality, race/ethnicity, class, abledness, citizenship/legal status, etc. are negotiated.

Bibliography

Barker, Chris: Cultural Studies and Discourse Analysis: A Dialogue on Language and Identity. London: Sage

Fairclough, N. (1989): Language and Power. Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press

Fairclough, Norman (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Longman.

Lazar, Michelle (2007): ”Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis: Articulating a Feminist Discourse Praxis,” Critical Discourse Studies 4: 2, 141 — 164. DOI: 10.1080/17405900701464816

Leeuwen, Theo van (2008): Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford UP

Wodak, Ruth (2009): Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE

- DozentIn: Eva Nossem